World Architecture Magazine – No.364

Habitat for Orphan Girls (Khansar, Iran)

A fourfold of strategic decisions drive the architecture of a shelter in City of Khansar for orphaned girls:

1. The “undue” is “undone”

In response to the financial limitations of the project, an austere, and honest tectonic is adopted. All superfluous layers of finishing and ornamentation are considered as “undue”, and hence, are eliminated.

2. The “oppressed” is “liberated”

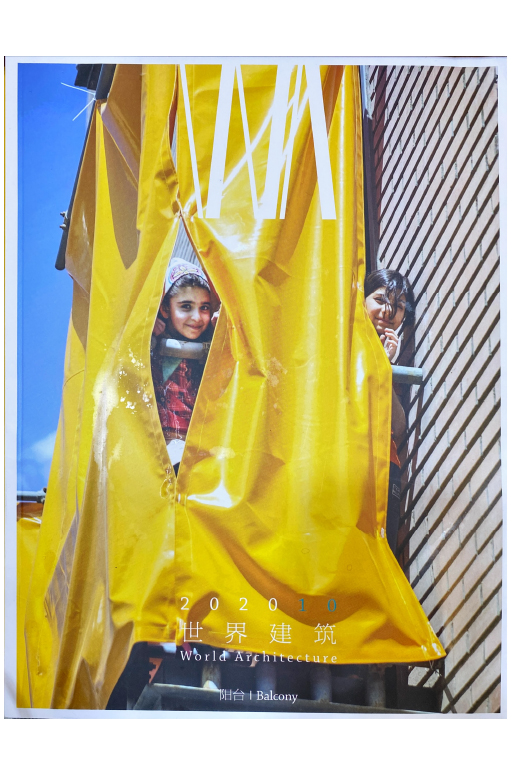

It is hard to exercise one’s right in choosing one’s lifestyle as an orphaned girl in a male-dominated religious city such as Khansar. In a critique of the status quo, although the architecture of the shelter adopts an introverted typology in response to concerns of security and security of the girls, the facade of the project transforms to a medium that allows the building to close down or open up to the city as the girls need or desire, capitalizing on the hand-operated exterior curtains of the balconies. As the girls learn how to operate the building, they exercise their limited rights over their practice of life.

3. The “past” is the “future”

The site of the project is located within the historic fabric of the city. The project was proposed to the owner of the site by the design team. Urban heritage, as a construct of culture, has the potential to initiate financial prosperity for the city and its inhabitants. As such, the past of the city becomes the future of its orphaned inhabitants.

4. The “not-house” becomes the “House”

The shelter is designed like a house to respect the basic human needs of the inhabitants of it; the need for privacy and a sense of belonging. As such, the shelter accommodates private rooms as well as social spaces for the girls.

Iranians say that they have two lives: one inside the home, where they can do as they please, and one outside, where they have to assume a high degree of decorum. In Iran, the home is a place where the state does not interfere. However, these children effectively live with the state. Excessive caution is taken to ensure their safety from kidnap and trafficking, which haunt vulnerable children such as these, and with that comes a restriction that the most girls their age do not have. This vulnerability excludes them to some degree from civic life. “These girls are not allowed to go outside into the town as they please, so instead of shutting out the outside world, we thought why we don’t bring the town inside to them?” Ghodousi says. State officials were staunchly against the idea of these balconies and fought to prevent them. The highly charged negotiations finally led to a compromise: the balconies would be built, but to appease the officials they would be covered in ‘hijabs’- sliding curtains, which could be adjusted to conceal or reveal. With this act, the balcony became an empowering threshold space between inclusion and exclusion.

“I never doubted that the girls would eventually claim the balcony for themselves,” Ghodousi confides. Like other children of their age, these girls are torqued by social forces like the pressure to get married, to live up to standards of beauty and to adopt outward displays of religiosity. The balcony is a place for them to have a moment for themselves.

Comments

QING Feng: The real shock may not be the balcony but the subtle “veil”. It recalls the small window for women to peep at the suitors through in Huizhou-style dwellings. It is hard to imagine balconies being such a sensitive element in our early life. It highlights the semi-public nature of the balcony. In contrast, a few windows on the outer walls are tightly covered by the dark-grey iron door. Under these conditions, the folds and undulations of the yellow draperies become extremely important, giving children more opportunity to look out on the street. When the firm walls and soft curtains form an appealing contrast, we feel the sense of architecture in the design of the balcony. (Translated by Dandan Wang)

ZHOU Jianji: Balcony as a medium. The balcony in the Iranian habitat for Orphan Girls reminds of some classic scenes, such as Juliet’s balcony or Mussolini’s speech. The balcony became a stage, and the performance put on the stage is far more important than the setting itself. The “presence” denoted by the balcony is worthy of attention. In this case, it is not a specific person who is “present”, and the rise and fall of the manually operated curtain become the most direct expression of will. These balconies in the internal and external circles have also become metaphors for these girl’s living conditions: independent, small, in a critical state of blending and isolation, but they are eager to express. After centuries, this balcony has returned to its original function- becoming a medium and transmitting messages.