The Architectural Review

Habitat for Orphan Girls (Khansar, Iran) is published on the The Architectural Review website.

Veiled in Secrecy: The Habitat for Orphan Girls by ZAV Architects, Iran

AR House winner 2018: set in the foothills of Iran’s Zagros Mountains, this girls’ orphanage gives vulnerable children a safe and culturally sensitive environment to grow up in.

This simple and elegant design by ZAV Architects, for the late philanthropist Dr. Ahmad Maleki, is a ground-breaking orphanage in Khansar, a small genteel town in the foothills of the Zagros Mountains. Some 180 miles south of Tehran, it is best known for its abundance of freshwater – which is remarkable considering its close proximity to Iran’s central desert. Despite being rich in resources, the once prosperous Khansar, like many places in Iran, is in economic straits, in part due to rural flight. Since the town relies heavily on revenue from tourism, the client wanted the Habitat for Orphan Girls to be nestled within the town’s historic monuments without causing disruption to the architectural integrity of the landscape. That sensitivity to context was shared by the ZAV team – Mohamadreza Ghodousi, Parsa Ardam, and Fatemeh Rezaie Fakhr-e-Astane – who, working with a limited space of 354m2, wanted to create a house that was very much at home with its surroundings.

The simple elegance of the four-story structure belies the complexities and controversies of the project. Khansar is an exceedingly conservative place and state representatives made highly restrictive demands, according to the client’s business partner, Javad Mirbagheri. ‘They said that every orphanage in the country followed the same nondescript blueprint and there was nothing we could do.’ The blueprint was a dorm-like building where all the girls lived and slept in one room on the same floor as the director’s room. Whether having all the girls in one room was in the interests of practicality, or perhaps due to a form of control or surveillance, the client wasn’t having it. With the threat that the land would no longer be bequeathed, the officials eventually acquiesced.

The Habitat for Orphan Girls is the first of its kind in Iran. ‘By advancing an alternative, we hope that this can be a future prototype for new forms of domesticity’, Ghodousi explains, adding, ‘and more broadly, new ways of thinking about family.’

But new doesn’t necessarily mean a radical departure from the past. On the contrary, Persian vernacular – a system of architecture that has developed over centuries as a response to Iran’s climatic conditions, locally available material and cultural codes – is in the building’s DNA. Persian vernacular doesn’t mean incorporating first-degree symbols of local history to give a building a ‘Persian identity’ – in fact, that sort of thinking is anathema to ZAV Architects. Rather a connection to the past is forged indirectly by designing in context.

For instance, residential houses in the Persian and Islamic traditions follow the principle of introversion, which means that the exterior of the house (biruni) receives greater restraint and far less ornamentation than the interior of the house (andaruni). The exterior is often shaped with geometric elements to signify harmony with the sacred world. With respect to the Habitat for Orphan Girls, the facade of the house features elegant inward-facing curves which were coordinated with the elevation and geometry of the arches along the hillside.

Harnessing the principle of introversion, the architects built nontransparent walls surrounding the perimeter – an Islamic obligation to guard against the eyes of strangers. The need for privacy takes on more significance in all-female areas because the walls ‘protect’ the chastity of females. The building’s walled courtyard, which includes a playground, allows the girls to feel the natural sunlight on their skin without the interference of interlopers. Another nod to the vernacular is the shallow pool (howz) in the courtyard; a transcendent element that is quintessentially Persian. In the vernacular, the pool is placed in a lush garden of trees, herbs, and plants, which holds cosmic symbolism in the Iranian cultural imagination. The architects included some sparse vegetation in the garden, restrained by the limited space, though it has grown a little since the house was first built. The how reflects the sky, adding a contemplative, spiritual dimension. The children love this area and try to spend as much time as they can here, playing in the water to escape the summer heat.

The visual privacy offered by this sense of enclosure in a typical Persian house creates a strong sense of solidarity among family members. You certainly feel this at the Habitat for Orphan Girls, as the girls readily refer to one another as a family and show displays of affection for their peers and their director. ‘Everyone deserves a house with dignity, and these girls, who don’t have a family to rely on, deserve it more than anyone else,’ says Ghodousi.

The ground floor of the building is an open-plan lounge dedicated to group gatherings, while the first floor houses auxiliary spaces such as the communal kitchen, the mechanical room, and the director’s suite. The six bedrooms – each with a balcony and accommodating up to 15 girls ranging in age from seven to 15 years – are located on the floor above the director’s room and accessed by ascending a narrow concrete staircase: a significant departure from the prescribed, state-sanctioned blueprint. The trio achieved an impression of continuity between the exterior and interior of the building by using the same cost-effective and local materials such as unprocessed brick and timber, reducing transport costs and energy consumption. Though materially simple and minimal, with the use of natural light and airiness the spaces feel homely and warm and have a ‘lived-in’ quality. The smells of Persian stew and the high-pitched chatter of the girls float through the building.

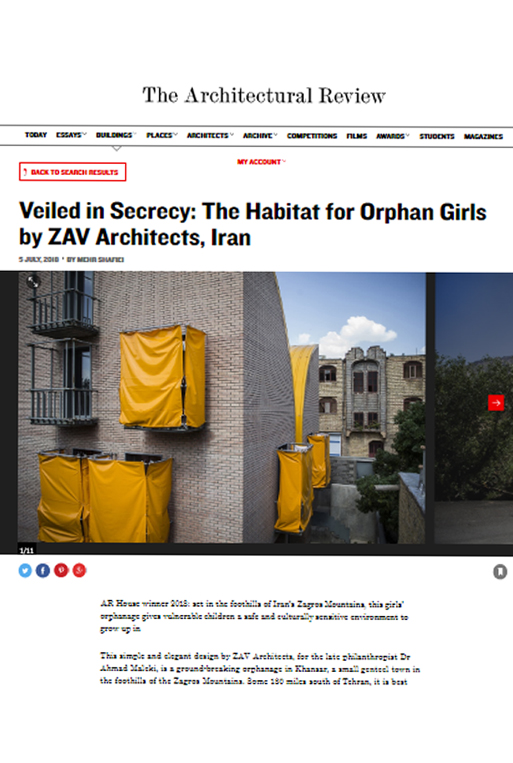

‘It makes me proud’, says 10-year-old Maryam, ‘I especially love the yellow that covers the roof. The house is beautiful.’ And though Ghodousi is happy that the girls like the aesthetics of the house, he downplays the stylistic eloquence of the building. Ever the artisan, he couches his philosophy in the language of ethics and craft – not art for art’s sake: to be driven by stylistic appearances is an attempt to aestheticize or romanticize the precarity of the orphans’ situation. For ZAV, the orphans’ lived experience is the yardstick by which to measure the building’s merits.

Each morning the girls wake each other up, take turns doing ablutions, and await the call to prayer played from loudspeakers emitting from the mint-green mosque next door. After is a communal breakfast of tea, bread, cheese, and honey – the town’s specialty. When they are not in school, they spend hours lounging around, playing, or studying. It is in the bedrooms that the children can exert a sense of control and autonomy, and it is where important and personal conversations take place. And the girls talk constantly, occasionally braiding one another’s hair. Although there is no Farsi translation for the term ‘angst’, a few of the teenage girls spend hours gazing blankly from the balcony – the kind of soul-searching that comes from enjoying the miles of rolling hills fragranced by wildflowers and fig trees.

‘The simple elegance of the four-story structure belies the complexities and controversies of the project. Khansar is an exceedingly conservative place and state representatives made highly restrictive demands’

Iranians say that they have two lives: one inside the home, where they can do as they please, and one outside, where they have to assume a high degree of decorum. In Iran, a home is a place where you have security and freedom – it is a place where the state does not interfere. However, these children effectively live with the state. Excessive caution is taken to ensure their safety from kidnap and trafficking, which haunt vulnerable children such as these, and with that comes a restriction that most girls their age do not have. This vulnerability excludes them to some degree from civic life. ‘These girls are not allowed to go outside into the town as they please, so instead of shutting out the outside world, we thought why we don’t bring the town inside to them?’ Ghodousi says. State officials were staunchly against the idea of these balconies and fought to prevent them. The highly charged negotiations finally led to a compromise: the balconies would be built, but to appease the officials they would be covered in ‘hijabs’ – sliding curtains, which could be adjusted to conceal or reveal. With this act, the balcony became an empowering threshold space between inclusion and exclusion.

‘I never doubted that the girls would eventually claim the balcony for themselves,’ Ghodousi confides. Like other children of their age, these girls are torqued by social forces like the pressure to get married, to live up to standards of beauty and to adopt outward displays of religiosity. The balcony is a place for them to have a moment for themselves.